Commissioned by President Emmanuel Macron, the report is an attempt by the French state to come to terms with its 132-year, often brutal occupation of Algeria and promote reconciliation between the two countries. But it stopped short of apologising for France’s actions. When the relationship between a former colonial power and its colony is examined, the focus is almost exclusively on repentance — whether the coloniser has done enough to atone for its past and how far it has fallen short. From a moral or historical point of view, this is legitimate because the coloniser carries the burden of its often violent occupation. But if we truly want to understand the bond of domination — which distorts the idea of justice — this approach is shortsighted. Focusing exclusively on the sins of the coloniser fixes the colonised in a state of perpetual victimhood.

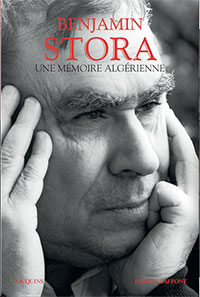

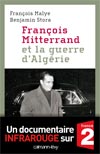

But this remains the approach of western academics, intellectuals from former colonies now residing in the former colonising state, and of elites in the former colony, who exploit the colonial past to further their own interests. Historian Benjamin Stora with French president Emmanuel Macron who is holding the Stora report on France’s 132-year occupation of Algeria © Christian Hartmann/POOL/AFP/Getty But being a “victim” prevents us from seeing how the memory of colonisation is manipulated by political and economic elites in former colonies, who lay claim to the legacy of the revolution. The west sees the world through its guilt, as it once saw it through its desire for domination. Guilt may be harmless, but it prevents understanding, which is needed for both parties to move forward. There is global interest in the case of France and Algeria because of the violent history of their relationship, the geographic proximity of the two countries, the sizeable Algerian immigrant communities in France and recent jihadist attacks on French soil, when terrorists used religion but also colonial-era injustices suffered by their Algerian parents to justify their actions. But we should not forget that the issues of guilt and reconciliation also concern the former colony.

What should Algeria do with its own history, which is so often distorted by “liberators” looking to further their own interests? How should it interact with its former colonial power? Kill it? Do business with it? Demand reparations? Love, or ignore it? Try and destabilise it, or rely on it for economic development? Algeria is closed for business. Entry visas are rare and the nation’s image remains frozen, like a museum to the glory of a people who took up arms for freedom. This narrative glosses powerfully over the present. The world knows almost nothing of daily life in the country and above all, overlooks the way its colonial past is used domestically. As an Algerian, it is amusing to be asked for an opinion about how France is coming to terms with its legacy of occupying my country — and how my countrymen and women should react to the lack of an apology for the past that we are assumed to be waiting for. But for a regime that has built its legitimacy on a specific narrative of the war of independence that cannot be challenged — and which it is keeping alive at all costs — an apology would be disastrous. In Algeria, Islamists, progressives, secularists and conservatives may not agree on most issues, but they are united when it comes to denouncing France. And it is this reality that the Stora report is shaking up. As soon as it was published, the text was deliberately misunderstood. Many in Algeria accused Stora of refusing the idea of an apology, although he said he “had no problem” with it. They also ignored a recommendation that there should be another report written by an Algerian counterpart, appointed by the Algerian presidency — which has yet to issue a response.

The Stora report has allowed Algeria to return to war with France over what took place decades ago, once again focusing on the eternal enemy and mobilising crowds. But underneath, the regime is panicking over what it has always feared — that this chapter will one day be closed and that it will have to begin to acknowledge — and take responsibility for — its past in order to build a powerful and happy nation.