By Scott Sayare (The New York Times, 28 Mars 2014) - The Saturday Profile.

TRADUCTION

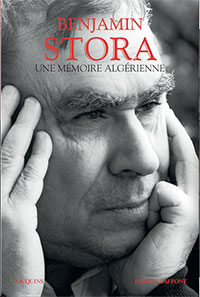

Asnières-sur-Seine, France - Benjamin Stora arrived in Paris in the summer of 1962, a boy exile swaddled in as many layers of clothing as his parents could fit on his little body. He came amid a flood of refugees, one million French colonists, Arabs and Jews fleeing the murderous tumult of revolutionary Algeria.

His family, suddenly destitute, brought with them as much of their homeland as they could. But Mr. Stora learned quickly not to speak of Algeria, he said. To do so would make him a reminder of France’s national disgrace, he feared, an emblem of the brutal, failed war to keep Algeria under the yoke of the receding French empire.

He trundled off to school and, with a sense of isolation and resentment that he was then too young to understand, set about forgetting.

France did the same. The forgetting of the Algerian war, a campaign begun in 1954 that left at least 400,000 Algerians and 35,000 French dead, in fact began well before the fighting ended in 1962. The conflict was inglorious in both aim and execution — the French made routine use of torture, for instance — and censors hid much of it from the populace, seizing newspapers, books and films deemed dangerous to national morale.

Only in 1999 did France officially recognize the fighting as a war at all, and only since then has the conflict entered school textbooks here. Though more than two million French soldiers were sent to fight, memorials are scant.

Mr. Stora, 63, has made a life of remembering, at first despite himself, later by conviction. A prolific historian, he is perhaps France’s foremost chronicler of the Algerian war, of its unavowed forgetting, and of the ways in which it continues to shape modern France: in the country’s discomfort over immigration and Islam, in its nostalgia for a more triumphal past, in its confusion over national identity. If France has begun a more honest reckoning with its colonial era, it is due in no small part to Mr. Stora, to his three dozen books and films and to his dogged belief that Algeria remains a toxic force here.

“We still haven’t taken the full measure of how much this war, this history, this French presence in Algeria, has marked and traumatized French society,” like a bitter “family secret,” Mr. Stora said. “Everything — everything — stems from Algeria.”

Algerians and North African Arabs constitute France’s largest immigrant population by far, making a confrontation with the past all the more uncomfortable and pressing, he said.

Mr. Stora studied Algeria well before such work was considered desirable; at the time, in the 1970s, open discussion of collaboration during the Nazi occupation was only just beginning. Now a pleasantly rumpled man with a round belly and a grave brow, he has helped train a generation of researchers. His best-known work, “Gangrene and Forgetting,” published in 1991, was among the first books to address the unspoken memory of the war. “Denial” was “eating away like a cancer” at France, he wrote.

“Stora’s book said openly what a lot of people had been thinking and feeling,” said Joshua H. Cole, director of the Center for European Studies at the University of Michigan.

More recently, Mr. Stora has turned to popular histories, often with particular attention to the traumas the war left as its legacy. “He’s done it with a certain empathy,” said Mohammed Harbi, a French-Algerian historian.

His work has been a form of personal psychotherapy as well, Mr. Stora said, helping him to enter a French society for which he never “held the social codes.” An Algerian-born French Jew, he calls himself a “sort of stateless person.” His work has helped, too, to untangle the knot of shame and pride that he long felt toward the land of his birth.

“He’s given Algeria back to us all,” said Annie Stora-Lamarre, his sister and a fellow historian.

Their family fled Constantine, a city with a once-boisterous Jewish quarter, set above gorges that echoed with gunfire during the war. In Paris, they lived in a garage for two years. Mr. Stora would bring friends to the entryway of a grand building next door, presenting it as his home, but never inviting them in.

His mother, from a family of jewelers, worked on a Peugeot assembly line, as did Mr. Stora briefly. His aging father found work at an insurance company. His sister became a typist at 16.

“We were thrown completely out of history,” Mr. Stora said.

The “pieds noirs,” the French inhabitants of colonial Algeria, were met with disdain in mainland France. Many were poor to start, and had fled Algeria with even less. Their resentment toward Algerians, but also toward the French government, which they felt had betrayed them, is deep even now.

SO, too, is that of the Harkis, Algerians who fought for the French. Perhaps 80,000 Harkis and family members fled to France in 1962, by Mr. Stora’s estimation, only to be held for years in internment camps. Many more were left behind; thousands, if not tens of thousands, were slaughtered as “traitors.”

Meanwhile, the French government excused itself and its soldiers of any possible wrongdoing, with a succession of amnesties.

“The French had to forget in order to live,” Mr. Stora said.

A sense of revolt drove Mr. Stora into radical politics, he said. He joined a Trotskyist group and studied the Algerian conflict because it was a revolution, he said, and “I was a revolutionary.”

Still, after a childhood of exile and poverty, his central preoccupation was with finding steady work, he said. He became a professor, a state position he has now held for 35 years. (He has abandoned proletarian internationalism.)

In the 1990s Algeria fell into a decade of civil war, and he was called upon frequently to explain the violence, some of which reached French soil, with bombings in Paris in 1995. He received death threats — from whom remains unclear — and the French security services moved his family. They stayed in Vietnam until 1997, a second exile of a sort.

Algeria has for years demanded an official apology from France for colonization, but it has not come. Just a few years ago, the French legislature passed a law, later repealed, that would have had schoolteachers emphasize France’s “positive role” in its former colonies.

There has been a shift, though. In what Mr. Stora deemed the first “great speech on colonization” by a French president, François Hollande in 2012 called for an end to French and Algerian “denial.”

“The truth does not damage,” Mr. Hollande declared. “It repairs.”

Still, the French tend to ruminate over their past, Mr. Stora said. “Either we’re in a glorious past, reconstructed and fantasized, or we’re in a past of denigration and misfortune, in which one can find one’s pleasure as well.”

He has resolved his own story, he said. He travels often to Algeria, and he has returned to Constantine to stand at the grave of his grandfather. His name, too, was Benjamin Stora.

Mr. Stora would like to study something else now, he said, or perhaps take up a new line of work. But society “always draws me back to Algeria,” he said with a bit of exasperation.

“At a certain point you say to yourself, ‘All this memory, all this accumulated knowledge — is it not time, today, to step outside of it?' ” he asked. “Shouldn’t we step outside of it?”